Visionary Development or Simple Land Grab?

Solano County Land Dealings

What is unfolding in Solano County, California promises to be an epic story of land, culture, and power; and so it begins—“Silicon Valley elites revealed as buyers of $800 million of land to build utopian city,” as The Guardian headline tantalizes.

It seems a secretive business entity has been purchasing land across the central to southeastern portion of Solano County for years now, amassing over 50,000 acres of land located only an hour’s drive north of San Francisco. Recent reports indicate this discreet effort started with the notion of reimagining what a sustainable city might look like and be. Investors were invited to join an audacious development venture that would apply the most cutting-edge design and build methods, technologies, and governance theories to create a truly sustainable city. Since at least 2018, agents have been quietly soliciting Solano County landowners and strategically purchasing parcels to aggregate large swaths of landscape, sometimes paying five-times the fair market rate. Five years later, with over $800,000,000 invested and 54,000 acres of hills and plains procured, the mystery of who is behind these stealthy dealings has now come to light. The entity is Flannery Associates, and it is fueled by Silicon Valley tech moguls and venture capitalists. But to what end?

Continue reading ...

The Best of Times for a Few, The Worst of Times for Most

As a land trust practitioner who has spent decades working with landowners, communities, planners, ecologists, farmers, advocates, and philanthropists, I am captivated by this story and the endless lines of inquiry and conflict it invokes. But behind the shining vision and rousing struggle that emerges around any idea of this scope and scale, I cannot help but see a plain and very old form of wealth capturing—land speculation. Who knows what will unfold in the years ahead. But two things seem all but certain. One, this is an effort that will go on for decades, as Flannery freely admits and is planning for; and two, in twenty to thirty years, the value of these 50,000 acres will be exponentially greater than today even if there is never a single road or building constructed.

A 2023 real estate report by the North Bay Business Journal shows that the Solano County median home price tripled from roughly $200,000 to $600,000 between 2000 and 2020. On top of this, the Bay area’s challenges with housing affordability and availability are well chronicled, to the point that, “San Francisco housing shortage,” “Homelessness in San Francisco Bay area,” and “Affordable housing in Silicon Valley” each have their own Wikipedia pages. Silicon Valley tech companies’ interest in creating affordable housing in communities where their growing employee bases live is also well known. As this 2018 headline from the Insider reads, “Facebook, Google, and LinkedIn are investing hundreds of millions in housing projects across North America.” Furthermore, real estate pressures are being exacerbated by broader social and environmental trends, such as remote work, food system adaptation, renewable energy development, sea level rise, and extreme heat, drought, and wildfire. All considered, a land investment such as this seems a matter of simple calculation, which derives very little speculative risk. The only speculation here is perhaps the rate and pace of returns.

With the volatility of our world today and its reflection in the markets, it is not surprising that these wealthy investors see land as a means of perpetuating and expanding their colossal fortunes. This is an old, well-documented play. Historian Gustavus Myers captures it plainly in his, History of the Great American Fortunes, Volume I, published in 1910 near the end of Second Industrial Revolution and the triumph of the Robber Barons. In Myers’ words,

“fortunes based upon land in the cities were indued with a mathematical certainty and perpetuity. … land was the one great auspicious , facile and durable means of rolling up an overshadowing fortune.”

Indeed, land as an asset class seems to be of increasing interest to today’s wealthy elites. In 2011, billionaire hedge fund manager and environmentalist, Jeremy Grantham, wrote prophetically about U.S. farmland and soil conditions in a lengthy quarterly letter to investors. Ten years later, The Land Report announced that Bill Gates— “Farmer Bill” as the Report called him—was the single largest private farmland owner in the country, with land holdings in 19 different states totaling over 268,000 acres. Then there is the Telosa project of billionaire, Marc Lore. Like Flannery Associates, Lore is promoting the creation of a new utopian city from the ground up. While Lore has stated unequivocally that Telosa is not a money-making venture, he acknowledges that a tremendous amount of wealth would be created in land value as the city expands from 30,000 acres to 150,000 acres over three decades. The intention for Telosa, however, is that the land would be owned collectively by its community members, and any wealth created would run to the benefit of the community not private landowners.

Perhaps Mr. Lore is familiar with Henry George’s, Progress and Poverty. This seminal work was published in 1879 at the emergence of the Gilded Age. Subtitled, an inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions, and of increase of want with increase of wealth, it identified and detailed how land speculation was the primary reason for periods of economic depression and associated urban squalor. The remedy for the inequitable and unjust conditions of the times as shown through George’s work was clear— “we must make land common property.” This work carried forward that of social reformers from a hundred years earlier at the turn of the eighteenth century. European thinkers of the time challenged the fundamental validity of land ownership. In 1795, Thomas Paine wrote Agrarian Justice, claiming,

“There could be no such thing as landed property originally. [Humans] did not make the earth, and though [they] had a natural right to occupy it, [they] had no right to locate as [their] property in perpetuity any part of it: neither did the Creator of the earth open a land office from whence the first title-deeds should issue.”

Fourteen years later, the philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudon would publish his stirring social and philosophical study titled, What is Property? He opens his tome with the results of the inquiry into this question stated baldly, “Property if theft!,” states Proudon, as surely as “slavery is murder.” A bold and antagonistic statement to make amid an ‘enlightened’ society in any age.

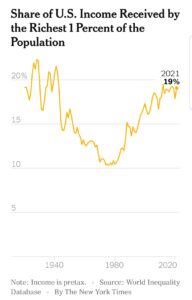

It is perhaps not coincidence that land and wealth are currently mingling in a way reminiscent of centuries past. The current income distribution in the US, with extraordinary wealth concentrations at the very top and burgeoning poverty at the bottom, is as close to turn-of-century disparities as we have ever experienced. Coincidently, the chart published in the New York Times just a few days ago helps illustrate the point. Are the efforts in Solano and Telosa just a return of an old impulse that accompanies such patterns of extraordinary wealth accumulation? Journalist and author, Steve Fraser, explored the “utopian ambitions” of the industrialist tycoons of the gilded age in his 2015 book, The Age of Acquiescence. After chronicling the efforts of George Pullman, Elbert Gary, and the technological wonders of the “White City” constructed for 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Fraser writes,

It is perhaps not coincidence that land and wealth are currently mingling in a way reminiscent of centuries past. The current income distribution in the US, with extraordinary wealth concentrations at the very top and burgeoning poverty at the bottom, is as close to turn-of-century disparities as we have ever experienced. Coincidently, the chart published in the New York Times just a few days ago helps illustrate the point. Are the efforts in Solano and Telosa just a return of an old impulse that accompanies such patterns of extraordinary wealth accumulation? Journalist and author, Steve Fraser, explored the “utopian ambitions” of the industrialist tycoons of the gilded age in his 2015 book, The Age of Acquiescence. After chronicling the efforts of George Pullman, Elbert Gary, and the technological wonders of the “White City” constructed for 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Fraser writes,

“Each such town was a display of dynastic preeminence. … The tycoon, Napoleonic in ambition and self-regard, felt empowered by his own mighty presence to reorder and heal the world under his personal diktat.”

While the White City may have heralded the coming of electric lighting, its orderly pastoral promise was essentially fantasy, and it mocked Chicago’s suffering urban masses. The conditions in Chicago at the time were very much shaped by the tycoon, Marshall Field, whose fortune and methods are described in the History of Great American Fortunes, referenced above. In Myers’ words,

“Field’s fortune was heaped up … This extension and centralization of land ownership were accompanied by precisely the same results as were witnessed in other cities … Poverty grew in exact proportion to the growth of large fortunes … Chicago became full of slums and fetid, overcrowded districts.”

A hundred-thirty years later we have one the largest populations of unhoused people in the country adjacent to the overshadowing wealth of Silicon Valley.

Seeing Land Through New Eyes

As an eternal optimist, I refuse to believe that the mingling of wealth and land today is a return of land speculation, primitive accumulation, and social pathology. The efforts around Solano and Telosa as well as the large land purchases by the wealthiest members of society across the country can be something different, an innovative start of a better way. “What change may come no mortal [person] can tell, but that some great change must come, thoughtful [people] begin to feel,” this line from the end of Progress and Poverty seems as apt today as in 1879. As a boy, I played pond-hockey during the long cold winters of New York’s Finger Lakes Region. I recall my dad’s words-of-wisdom as I headed out with stick and skates in hand, “Have fun!”, he would say, “And if you ever find yourself on thin ice, lay flat, and have your friends do the same; then work together to carefully ease your way to solid ground.” It seems we are all on thin ice at the moment. Great change is indeed upon us, and we risk breaking through to climatic conditions for which we are wholly ill equipped and unprepared to survive. This is a moment that calls for collective action with awareness and care for each other, spreading the load, and seeking safety in healthy land together.

The challenging times ahead ask that we begin to relate differently to land, that we move beyond the dominant paradigm of land as property, asset, and commodity, and start fostering the notion of land as gift, life, and shared home. From this perspective, land is not for ownership but for stewardship. The extreme weather conditions we are all experiencing will only continue, and likely worsen, in the decades ahead. 2023 has been the worst year on record for natural disasters in the US, with 23 events that each caused over a billion dollars’ worth of destruction. These disasters total over $57,000,000,000 and we have not yet entered the eye of hurricane season—$57 billion! This is more than the entire Gross National Product of Libya, a country that is grappling with the shock and devastation of a singular flooding catastrophe that compromised aging dams and killed over 11,000 people. As I write, hurricane Lee bears down on the coast of Maine, the first hurricane likely to make landfall in Maine in over 50 years.

There is no path forward to a resilient and sustainable future that does not include working with nature to restore the natural capacities and cycles of terrestrial and hydrologic systems to help mitigate atmospheric carbon and adapt a much more volatile world. A team of more than 200 scholars, scientists, policymakers, business leaders, and activists convened by Project Drawdown to vet and disseminate a comprehensive list of the most substantive and viable solutions to climate change included over 30 focus areas associated with land, water, and agriculture. Such solutions included forest protection, wetlands restoration, Indigenous Peoples’ land stewardship, regenerative agriculture, silvopasture, afforestation, managed grazing, and perennial biomass, to name but a few. In the measured language of the IPCC’s Special Report Land and Climate Change, “the Earth’s land area is finite. Using land resources sustainably is fundamental for human well-being;” or in the eloquent and powerful words of scholar, author, and Potawatomi elder, Robin Wall Kimmerer, “here is where our most challenging and most rewarding work lies, in restoring a relationship [with land] of respect, responsibility, and reciprocity. And love.” We can no longer afford to hold the antiquated notion of land as an inanimate fragment of ground to be used, wasted, or disposed of at the whim of a single person or corporation. It is far too vital for a livable future.

We will need the wealthiest members of society to engage with land in new and innovative ways, perhaps even to aggregate title and rights. But their efforts must be truly forward looking, inspired by land stewardship and an appreciation and respect for the entanglement and mutuality of all life, including our own—not speculative techno development that hearkens back to the “White City.” Proust once suggested that, “the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” I trust that the landscape ventures in Solano, around Telosa, and among the vast holdings of elite investors across the country are not for the blind expression of tired ideas and wealth accumulation but for the realization of visions seen through new eyes gained from personal discovery. Eyes that see past the false separation of humans and nature that has dominated the western worldview for millennia; eyes that are crystal clear about the daunting and pivotal moment of change that we are in together; eyes that can see the “shimmer” of land, or as Deborah Bird Rose describes, the Aboriginal aesthetic attuned to multispecies relations, the presence of the past, and the rhythms generated by this dance of life over time. Such a change of perspective would be a true disrupter, not for the purpose of profit and wealth, but for climate balance and cultural evolution.